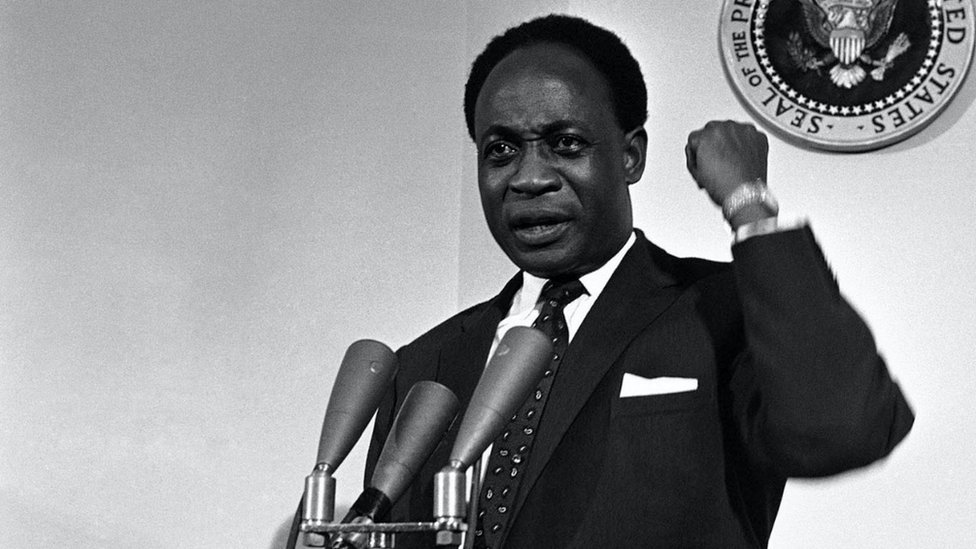

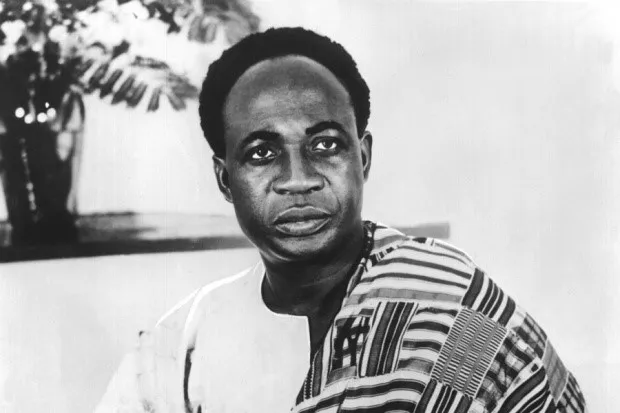

Francis Kwame Nkrumah (21 September 1909 – 27 April 1972) was a Ghanaian politician, theorist, and revolutionary. He served as Prime Minister of the Gold Coast from 1952 until 1957, when it achieved independence from Britain. Following this, he became Ghana’s first Prime Minister and later its President, serving from 1957 to 1966. A key proponent of Pan-Africanism, Nkrumah helped establish the Organization of African Unity (OAU) and was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize by the Soviet Union in 1962.

After spending twelve years abroad for higher education, shaping his political ideology, and collaborating with other Pan-Africanists, Nkrumah returned to the Gold Coast to champion national independence. He founded the Convention People’s Party, which quickly garnered mass support from ordinary citizens. Nkrumah became Prime Minister in 1952, a position he retained when Ghana gained independence in 1957. In 1960, a new constitution was adopted, and Nkrumah was elected President.

Nkrumah’s government embraced socialism and nationalism. It invested in industrial and energy projects, established a robust education system, and promoted Pan-Africanist ideals. Ghana, under his leadership, became a prominent voice in African international relations during the era of decolonization.

However, economic struggles and failed assassination attempts led to an authoritarian turn in Nkrumah’s governance during the 1960s. Political opposition was suppressed, and elections became neither free nor fair. In 1964, a constitutional amendment declared Ghana a one-party state, making Nkrumah president for life of both the country and its ruling party. He cultivated a personality cult, created ideological institutions, and adopted the title ‘Osagyefo Dr.’ In 1966, a coup d’état led by the National Liberation Council overthrew him, and the country’s economy was privatized under their regime. Nkrumah spent the rest of his life in Guinea, where he was honored as co-president.

Early Life and Education

Gold Coast

Kwame Nkrumah was born on September 21, 1909, in Nkroful, a small village in the Nzema region of the Gold Coast, now Ghana. The village was near the border with the French Ivory Coast. His father, a goldsmith, lived separately in Half Assini, working until his death. Raised by his mother and extended family, Nkrumah spent a carefree childhood exploring the village, bush, and sea.

As a student in the U.S., he was known as Francis Nwia Kofi Nkrumah, with “Kofi” marking his Friday birth. He changed his name to Kwame Nkrumah in 1945 while in the UK. The name “Nkrumah,” traditionally for a ninth child, suggests his father’s larger household. His father, Opanyin Kofi Nwiana Ngolomah, hailed from Nkroful and the Asona clan of the Akan Tribe. Respected for his wisdom, Ngolomah passed away in 1927.

Nkrumah was his mother’s only child. She sent him to a Catholic mission school in Half Assini, where he excelled. His mother, Elizabeth Nyanibah, was a fishmonger and petty trader, and her marriage to Ngolomah resulted in Nkrumah’s baptism into Catholicism in 1925. After excelling in his studies, Nkrumah trained as a teacher at Achimota School, where mentors like Kwegyir Aggrey introduced him to ideas of black empowerment.

After completing his teacher’s certificate in 1930, Nkrumah taught at a Catholic school in Elmina, became headmaster in Axim, and founded the Nzema Literary Society. In 1933, he taught at a Catholic seminary in Amissano, considering becoming a Jesuit. Influenced by Nnamdi Azikiwe, a prominent Nigerian nationalist, Nkrumah pursued higher education and left for the U.S. in 1935.

United States

Historian John Henrik Clarke observed that Nkrumah’s ten years in the U.S. shaped his worldview. He began studying at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania in 1935, securing a scholarship despite financial struggles. To sustain himself, he took various menial jobs and frequented black Presbyterian churches.

Nkrumah earned a Bachelor of Arts in economics and sociology in 1939 and later a Bachelor of Theology in 1942. He pursued further studies at the University of Pennsylvania, earning a Master’s in philosophy and another in education by 1943. During this time, he also worked with linguist William Everett Welmers on the Fante dialect of Akan.

In Harlem, Nkrumah engaged with the vibrant intellectual and cultural scene, absorbing ideas from street speakers and activists. He led the African Students Association of America and Canada, advocating Pan-African unity over individual colonial independence. His involvement in the 1944 Pan-African conference in New York further solidified his commitment to African liberation and development.

In 1945, Nkrumah decided to move to London to continue his education, supported by connections like Trinidadian Marxist C.L.R. James, who introduced him to political organizing.

London

In May 1945, Nkrumah arrived in London, enrolling briefly at the London School of Economics and later at University College London to study philosophy. However, his focus shifted to political activism. Alongside George Padmore, he organized the Fifth Pan-African Congress in Manchester, advocating for African socialism and a federated United States of Africa. The congress attracted figures like W.E.B. Du Bois and future African leaders, including Jomo Kenyatta and Hastings Banda.

Nkrumah became secretary of the West African National Secretariat, promoting decolonization and supporting stranded African seamen in London. He also founded the Coloured Workers Association. These activities drew surveillance from the U.S. State Department and MI5 due to concerns about Communist affiliations.

Nkrumah and Padmore formed The Circle, a group dedicated to achieving a Union of African Socialist Republics. Documents tied to The Circle, found during Nkrumah’s 1948 arrest in Accra, became evidence against him. Despite these challenges, Nkrumah’s time in London solidified his vision of a unified, independent Africa.

Return to the Gold Coast

United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC)

In 1946, a new constitution for the Gold Coast granted Africans a majority on the Legislative Council, marking a significant step towards self-government. This development led to the formation of the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC) in August 1947. The UGCC, comprised of successful professionals, aimed for rapid self-governance. They appointed Kwame Nkrumah as the party’s general secretary at the recommendation of Ako Adjei. Despite initial hesitation, Nkrumah accepted, recognizing the political potential of the role. After addressing concerns from British officials about his communist ties, Nkrumah returned to the Gold Coast in late 1947, beginning his work at the UGCC headquarters in Saltpond.

Nkrumah quickly proposed a colony-wide network of UGCC branches and the use of strikes for political objectives. This assertive approach caused tension within the party’s leadership, led by J.B. Danquah. Nkrumah’s efforts to expand the UGCC and raise funds further widened these divisions.

Discontent in the Gold Coast stemmed from inflation, cocoa crop destruction due to swollen-shoot virus, and unemployment among World War II veterans. This unrest culminated in the 1948 Accra riots, sparked by police killing three veterans during a protest march. The colonial government blamed the UGCC and arrested six leaders, including Nkrumah. Detention deepened rifts among the leaders, who accused Nkrumah of inciting the riots.

After their release, Nkrumah established the Ghana National College and launched initiatives such as the “Accra Evening News” and the Committee on Youth Organization (CYO), which championed the slogan “Self-Government Now.” The CYO, uniting students, veterans, and market women, became a powerful grassroots movement. Nkrumah foresaw an inevitable split from the UGCC and worked to consolidate support among the masses, leveraging liberation songs and rallies to amplify his appeal.

Convention People’s Party (CPP)

Under pressure from supporters, Nkrumah founded the Convention People’s Party (CPP) in June 1949. The CPP’s symbol, the red cockerel, and its colors—red, white, and green—resonated with the populace. The CPP’s grassroots campaigns reached beyond the urban elite, mobilizing widespread support for Nkrumah.

The British, meanwhile, sought to draft a new constitution granting greater self-governance. Nkrumah, dissatisfied with the proposed reforms, initiated a Positive Action campaign, calling for strikes and protests. This campaign led to violence and his imprisonment in January 1950. Despite being in prison, Nkrumah influenced CPP strategies through smuggled notes.

In the 1951 legislative election, the CPP achieved a landslide victory, winning 34 of 38 contested seats. Nkrumah, elected while imprisoned, was released and asked by Governor Charles Arden-Clarke to form a government.

Leader of Government Business and Prime Minister

Nkrumah’s administration prioritized unity across the Gold Coast’s diverse regions and accelerated development plans. Infrastructure, education, and public services were rapidly expanded, supported by financial reserves from cocoa profits. However, challenges like corruption and regional tensions emerged.

As Prime Minister in 1952, Nkrumah began constitutional consultations, culminating in a 1953 White Paper advocating for full self-governance. The CPP’s majority in the 1954 election solidified its mandate, but opposition groups, like the National Liberation Movement, called for federal governance and greater regional autonomy.

To resolve these disputes, another election was held in 1956, reaffirming the CPP’s dominance. In August 1956, the assembly voted for independence under the name Ghana. Despite ongoing regional concerns, Nkrumah maintained his vision of a unitary state. On 6 March 1957, Ghana became an independent nation and a full Commonwealth member, marking the end of colonial rule.

Ghanaian Independence

The old Gold Coast flag symbolized the dominance of the British Empire, while Nkrumah’s new flag for Ghana represented African nationalism and prosperity. Ghana gained independence on 6 March 1957 as the Dominion of Ghana, becoming the first of Britain’s African colonies to achieve majority-rule independence. This milestone attracted global attention, with over 100 journalists covering the celebrations in Accra. U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower extended his congratulations and sent Vice President Richard Nixon to attend the event. The Soviet Union encouraged Nkrumah to visit Moscow, and Ralph Bunche, an African American political scientist, represented the United Nations. The Duchess of Kent attended on behalf of Queen Elizabeth II. International offers of support poured in, though Ghana appeared economically strong, buoyed by high cocoa prices and promising resource development.

As the fifth of March transitioned into the sixth, Nkrumah addressed a massive crowd, declaring, “Ghana will be free forever.” Later, at the first session of the Ghana Parliament on Independence Day, he emphasized the nation’s responsibility to demonstrate that Africans could govern effectively, democratically, and with tolerance. His leadership earned him the title Osagyefo, meaning “redeemer” in Akan. The independence celebrations included notable figures such as the Duchess of Kent and Governor-General Charles Arden-Clarke, with over 600 reporters making it one of the most widely covered African events of the era.

The flag of Ghana, designed by Theodosia Okoh, drew inspiration from Ethiopia’s green-yellow-red Lion of Judah flag, replacing the lion with a black star. Red signified the blood of freedom fighters, green represented agriculture and natural beauty, yellow symbolized mineral wealth, and the Black Star stood for African liberation. Amon Kotei designed the nation’s coat of arms, featuring eagles, a lion, St. George’s Cross, and a Black Star, all adorned with gold accents. The national anthem, “God Bless Our Homeland Ghana,” was composed by Philip Gbeho.

To commemorate independence, Nkrumah inaugurated Black Star Square near Osu Castle in Accra. This space was designated for national celebrations and patriotic gatherings.

Under Nkrumah’s leadership, Ghana embraced some social democratic ideals, including the establishment of welfare programs, community initiatives, and new schools.

Ghana’s Leader (1957–1966)

Political Developments and Presidential Election

Kwame Nkrumah faced early challenges after Ghana’s independence. Tensions arose in Togoland after a contested plebiscite, prompting troop deployment. A bus strike in Accra escalated into riots, fueled by the Ga people’s belief that other tribes received preferential treatment in government promotions. In response, Nkrumah introduced the Avoidance of Discrimination Act (1957), banning tribal or regional political parties. This led to the destooling of Ashanti chiefs opposing the Convention People’s Party (CPP), raising concerns among opposition groups. These parties united under the United Party, led by Kofi Abrefa Busia.

In 1958, an opposition MP was accused of planning an armed rebellion. Fearing an assassination attempt, Nkrumah passed the Preventive Detention Act, allowing imprisonment without trial for up to five years, further damaging his reputation. The CPP also abolished regional assemblies through a constitutional amendment in 1959, centralizing power and bypassing judicial checks.

By 1960, Ghana transitioned to a republic, with Nkrumah elected president after defeating J.B. Danquah. A new constitution granted him broad powers and proposed integration into a Union of African States. Ghana remained part of the British Commonwealth under the new system.

Opposition to Tribalism

Nkrumah sought to combat tribalism, viewing it as a barrier to national unity and development. His administration passed legislation to restrict tribal and religious propaganda and banned tribal flags. Critics, including Kofi Abrefa Busia, viewed these measures as repressive, with Busia eventually leaving Ghana. Nkrumah’s leadership cultivated a cult of personality, earning him the title Osagyefo (“Redeemer”) and recognition as a global leader in African independence.

Nkrumah reduced the influence of traditional chiefs, particularly Akan and Ashanti leaders, who had cooperated with British colonial rule. By passing laws in 1958 and 1959, his government could destool chiefs and manage stool land revenues. These policies alienated traditional leaders, who later supported his political downfall.

Increased Power of the CPP

In 1962, three CPP members were accused of plotting to assassinate Nkrumah. Despite insufficient evidence, they were convicted after a second trial, following amendments allowing the president to dismiss judges. In 1964, Nkrumah secured a constitutional amendment declaring the CPP the sole legal party and himself president for life, effectively establishing a dictatorship.

Civil Service

After early efforts to Africanize Ghana’s civil service, the country saw an influx of foreign workers from Eastern Europe and other nations between 1960 and 1965, reflecting Ghana’s alignment with socialist states.

Education and Development

Nkrumah prioritized education as a cornerstone of Ghana’s development. The CPP introduced the Accelerated Development Plan in 1951, emphasizing universal primary education and technical training. By 1962, primary education became compulsory. The government took control of missionary schools and established new institutions, including the Kwame Nkrumah Ideological Institute (1961) to promote Pan-Africanism and train civil servants.

In 1964, Nkrumah unveiled the Seven-Year Development Plan, focusing on secondary technical education and vocational training. Employers were encouraged to contribute to labor training, supported by tax incentives. The Kumasi Technical Institute (1956) and subsequent initiatives furthered technical education.

Nkrumah championed science and technology as essential for building a socialist society. In a 1964 speech, he emphasized the need to involve all Ghanaians in scientific endeavors through education and public engagement. His vision integrated scientific discovery into daily life, aiming to foster national development.

Culture

Kwame Nkrumah, a dedicated pan-Africanist, viewed the movement as a pursuit of continental integration. His era of political activity marked a “golden age of pan-African ambitions,” as nationalist movements and decolonization surged. Nkrumah symbolized his African identity by wearing traditional fugu attire made from Kente cloth. He also prioritized cultural development, opening institutions like the Ghana Museum (1957), the Arts Council of Ghana (1958), the Research Library on African Affairs (1961), and the Institute of African Studies (1962).

Nkrumah’s government addressed social issues such as nudity in northern Ghana, deploying Hannah Cudjoe, who formed the Ghana Women’s League to promote nutrition, child-rearing, and clothing. The League protested French nuclear testing in the Sahara but was later marginalized within the party. Laws in 1959 and 1960 created reserved parliamentary seats for women, and opportunities expanded in education, professions, and the military. However, most women remained in agriculture, with limited support from the Co-operative Movement.

Nkrumah’s likeness appeared widely in a monarchic style, sparking accusations of a personality cult.

Media

In 1957, Nkrumah established the Ghana News Agency (GNA) to produce and share domestic news internationally. By 1967, the GNA managed extensive telegraph networks and had stations in major cities like London and New York. Nkrumah emphasized journalism as a tool for decolonization and unity.

State control of media intensified with the founding of the Ghanaian Times in 1958 and the acquisition of the Daily Graphic in 1962. He argued that capitalism distorted press integrity, justifying government control and pre-publication censorship. The Ghana Broadcasting Corporation (GBC) was revamped in 1954 and featured Nkrumah in broadcasts addressing societal issues. His initiatives included introducing a National Pledge, Flag Salute, and training programs for youth.

The GBC’s external service launched in 1961, broadcasting Pan-Africanist content in multiple languages to Africa and Europe. Refusing advertising, Nkrumah shaped media as a vehicle for education and national unity.

Economic Policy

The Gold Coast, one of Africa’s wealthiest regions, had advanced infrastructure and social systems. Nkrumah sought rapid industrialization to achieve economic independence by reducing reliance on foreign resources. His Second Development Plan in 1959 aimed to establish 600 factories.

The Statutory Corporations Act centralized major industries under government control, aligning with Nkrumah’s preference for state-led economics, further solidified after visits to socialist nations in 1961. Early successes included expanding agriculture and exploiting gold and bauxite reserves. The Volta River Project, centered on the Akosombo Dam, provided hydroelectric power, boosting industry and electrification.

However, financing the dam through foreign aid and higher taxes on cocoa farmers deepened regional disparities. Despite promoting industrialization, Ghana faced economic challenges, including fluctuating cocoa prices. A Seven-Year Plan in 1964 emphasized industrial modernization, yet the reliance on cocoa and external debt strained the economy.

Nkrumah also initiated nuclear energy projects, founding the Ghana Atomic Energy Commission and laying groundwork for an atomic facility in 1964.

Cocoa

The global cocoa boom in 1954 saw prices triple, but Nkrumah diverted the windfall into national projects, alienating cocoa farmers. Price volatility further impacted the government, forcing partial payments in bonds by 1965. The declining cocoa revenue exemplified Ghana’s economic vulnerabilities under Nkrumah’s leadership.

Foreign and Military Policy

Nkrumah strongly advocated Pan-Africanism, establishing international organizations to unify the continent. These included the First Conference of Independent States (1958), the All-African Peoples’ Conference (1958), the All-African Trade Union Federation (1959), the Positive Action and Security in Africa conference (1960), and the Conference of African Women (1960). Simultaneously, Ghana withdrew from colonial-era organizations like the West African Currency Board and the West African Court of Appeal.

In 1960, Nkrumah founded the Union of African States with Guinea and Mali, creating a women’s group, Women of the Union of African States. He also played a pivotal role in the Casablanca Group, advocating for African unity through political, economic, and military integration. Nkrumah was a founding member of the Non-Aligned Movement in 1961 and instrumental in establishing the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in 1963. His vision included a unified African military force, the African High Command, and a surrender of Ghana’s sovereignty to a continental union, outlined in the 1960 Republican Constitution.

Nkrumah supported the United Nations but criticized its susceptibility to the Great Powers’ influence. Opposing African countries joining the European Economic Community, he proposed an African common market and currency to attract international capital while reducing economic competition among nations.

Nkrumah leveraged Cold War rivalries between the United States and the Soviet Union to secure financial backing for projects like the Volta River Dam, showcasing Ghana’s strategic importance.

Armed Forces

Upon independence, Ghana inherited the British-led Royal West African Frontier Force. Concerned about military coups, Nkrumah delayed appointing African officers to top roles. However, he modernized the military by establishing the Ghanaian Air Force, acquiring aircraft from Canada and the Soviet Union, and creating training programs with international assistance. The Navy received British ships, including inshore minesweepers and corvettes, and officers trained in the UK.

Ghana’s military budget increased significantly, from $9.35 million in 1958 to $47 million in 1965. Ghana’s troops participated in the Congo Crisis as part of a UN mission, a challenging deployment that accelerated the transfer of officer roles to Ghanaians. Ghana also supported Rhodesian rebels fighting white minority rule.

Relationship with the Communist World

Nkrumah aligned with the Soviet Union and China during a 1961 Eastern Europe tour, adopting the Mao suit and earning the Lenin Peace Prize in 1962. His relationship with socialist nations emphasized solidarity and ideological alignment.

1966 Coup d’État

In February 1966, while Nkrumah was visiting North Vietnam and China, a coup led by the military and police, with alleged CIA involvement, ousted his government. The conspirators, called the National Liberation Council, ruled Ghana for three years. Nkrumah, informed of the coup while in China, later accused the U.S. of orchestrating it, citing documents shown to him by the KGB. Some CIA insiders later corroborated claims of American involvement, though they remain unverified.

Post-coup, Ghana distanced itself from socialist allies, embraced Western-aligned policies, and invited the IMF and World Bank to influence its economy. This shift diminished Ghana’s standing among African nationalists, particularly with its softened stance on apartheid South Africa.

Legacy

Analysts like Edward Luttwak argued Nkrumah’s downfall stemmed from his success in educating the masses and fostering political awareness. This progress spurred criticism of his regime, necessitating greater repression and propaganda to maintain control—efforts in which Nkrumah fell short. His achievements in economic development inadvertently fueled his regime’s collapse, overshadowing economic mismanagement as a cause.

Exile and Death

Kwame Nkrumah passed away on April 27, 1972, in Bucharest, Romania, due to an incurable illness. Following his overthrow, he resided quietly in Conakry, Guinea.

Tributes and Legacy

Nkrumah received honorary doctorates from several universities, including Lincoln University (USA), Moscow State University, Cairo University, Jagiellonian University, and Humboldt University.

In 2000, he was voted African Man of the Millennium by BBC World Service listeners, recognized as a “Hero of Independence” and a symbol of freedom for leading the first sub-Saharan African nation to gain independence.

U.S. intelligence documents revealed that Nkrumah was seen as a significant adversary to U.S. interests.

In 2009, Ghana’s President John Atta Mills established September 21 as Founders’ Day, later renamed Kwame Nkrumah Memorial Day in 2019.

An advocate of non-aligned Marxism, Nkrumah criticized capitalism’s impact on Africa, believing socialism aligned better with African traditions. In his 1967 essay “African Socialism Revisited,” he emphasized egalitarianism and scientific socialism.

A staunch pan-Africanist, Nkrumah was inspired by figures like Marcus Garvey, W.E.B. Du Bois, and George Padmore, forming relationships with them during his studies in America. His activism led to significant achievements, including the founding of the Organisation of African Unity. Intellectuals like Du Bois and Kwame Ture supported his efforts, and Nkrumah became a symbol of black liberation.

In his 1961 speech “I Speak of Freedom,” Nkrumah envisioned a prosperous, united Africa free from European exploitation. He urged immediate action, rallying nationalist sentiment.

Honors in his memory include the Kwame Nkrumah Memorial Park in Accra and the renaming of Ghana’s University of Science and Technology to Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology.

Personal Life

Nkrumah married Fathia Ritzk, an Egyptian teacher, in 1957. They had three children: Gamal, a journalist; Samia and Sekou, both politicians. Nkrumah also had an older son, Francis, a pediatrician.

Cultural Depictions

Nkrumah influenced figures like the grandfather of Wes Moore, author of The Other Wes Moore. He was portrayed by Danny Sapani in The Crown and featured in the 2011 film African’s Black Star: The Legacy of Kwame Nkrumah. His image also appeared in Ghanaian rapper Serious Klein’s 2021 music video.

Works

Nkrumah authored numerous books and essays, including Ghana: The Autobiography of Kwame Nkrumah, Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism, and I Speak of Freedom. His works reflect his vision of decolonization, African unity, and socialism.

Thank you for reading. Subscribe to Africarized YouTube channel, follow our Facebook page, Tiktok, X and Instagram.