Haile Selassie I: An Overview

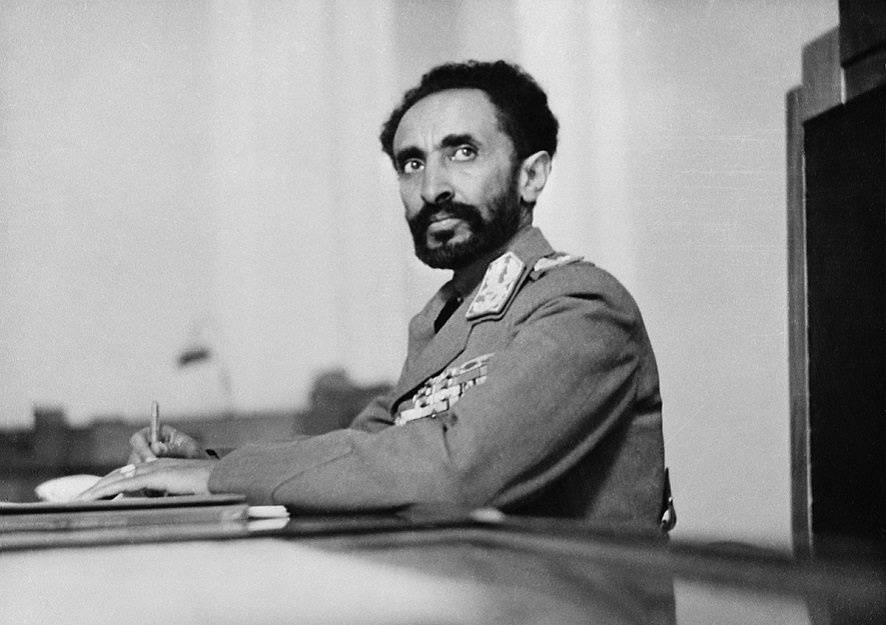

Haile Selassie I (Ge’ez: ቀዳማዊ ኀይለ ሥላሴ, meaning “Power of the Trinity”) was born Tafari Makonnen (later Lij Tafari) on July 23, 1892, and served as Emperor of Ethiopia from 1930 to 1974. Before ascending the throne, he acted as Regent Plenipotentiary under Empress Zewditu from 1916 to 1930. A central figure in Ethiopian history, Selassie holds divine status within Rastafari, an Abrahamic faith that emerged in the 1930s. Prior to his reign, he defeated Ras Gugsa Welle Bitul in the Battle of Anchem. Selassie was a member of the Solomonic dynasty, which claimed descent from Menelik I, son of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, though historians view this lineage as a political construct by Emperor Yekuno Amlak in 1270 to legitimize his rule.

Determined to modernize Ethiopia, Selassie implemented significant reforms, including the 1931 constitution and the abolition of slavery in 1942. During the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, he led Ethiopia’s resistance but was exiled to the United Kingdom after Ethiopia’s defeat. From exile, he coordinated resistance efforts and returned following the East African campaign of World War II. He later annexed Eritrea into Ethiopia, dissolving the federation established by the UN in 1950. An advocate for African unity, Selassie played a key role in founding the Organisation of African Unity in 1963 and served as its first chairman. He sought to moderate the anti-Western rhetoric of African socialist leaders like Kwame Nkrumah, envisioning a balanced approach to continental politics.

Selassie was overthrown during the 1974 Ethiopian coup d’état by the Derg, a Marxist–Leninist military junta backed by the Soviet Union. In 1994, after the Derg’s fall, it was revealed that Selassie had been assassinated at the Jubilee Palace on August 27, 1975. His remains were reburied in 2000 at Addis Ababa’s Holy Trinity Cathedral.

Among Rastafarians, Selassie is venerated as the returned Jesus, though he remained a devout Christian adhering to Ethiopian Orthodox beliefs. His reign faced criticism for suppressing revolts by the aristocracy (Mesafint) and for insufficient modernization. Groups like Human Rights Watch labeled his administration autocratic. Selassie’s policies also displaced Amhara populations into southern Ethiopia, and his government faced allegations of marginalizing the Oromo language, though no formal laws criminalized linguistic use. In 2020, following the assassination of Ethiopian activist Hachalu Hundessa, protests led to the destruction of Selassie’s bust in the UK and the removal of his father’s equestrian statue in Harar.

Early Life and Ascension Born Lij Tafari Makonnen, his childhood name “Lij” indicated noble lineage, while “Tafari” means “respected” or “feared.” He became Dejazmatch of Gara Mulatta at age 13, a noble title akin to count. In 1916, he was proclaimed Crown Prince and Regent Plenipotentiary and was crowned Le’ul-Ras in 1917, a rank equivalent to duke. In 1928, Empress Zewditu granted him the title Negus (“King”). After her death in 1930, Tafari was crowned Emperor (Negusa Nagast, “King of Kings”), adopting the regnal name Haile Selassie I, meaning “Power of the Trinity.” His official title reflected Ethiopian traditions linking monarchs to King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, as described in the Kebra Nagast.

To Ethiopians, Selassie was known by titles like Janhoy (“His Majesty”) and Talaqu Meri (“Great Leader”). The Rastafari movement further honors him with names such as Jah and Jah Rastafari.

Tafari’s Heritage and Early Life

Haile Selassie I, originally named Tafari Makonnen, descended from the Shewan Amhara Solomonic lineage through his paternal grandmother, tracing back to King Sahle Selassie. Born on 23 July 1892 in Ejersa Goro, Hararghe province, Tafari’s mother, Woizero Yeshimebet Ali Abba Jifar, was of Oromo and Silte heritage, while his father, Ras Makonnen Wolde Mikael, had Amhara maternal ancestry, though his paternal lineage is debated. Tafari’s paternal grandfather governed Menz and Doba districts in Shewa, while his mother hailed from Were Ilu in Wollo province. Ras Makonnen, a key general during the First Italo-Ethiopian War, enabled Tafari’s ascent to the throne via his grandmother, Woizero Tenagnework Sahle Selassie, an aunt of Emperor Menelik II. Selassie claimed lineage from Queen Makeda (Sheba) and King Solomon.

Tafari received education in Harar under Abba Samuel Wolde Kahin and Dr. Vitalien, and was appointed Dejazmach (“commander of the gate”) at age 13 on 1 November 1905. After his father’s death in 1906, he began his political journey.

Early Governorship and Marriage

Tafari’s initial governorship of Selale in 1906 was nominal, allowing him to continue his studies. In 1907, he governed parts of Sidamo province and allegedly fathered a daughter, Princess Romanework, with Woizero Altayech. Following his brother Yelma’s death, Tafari became governor of Harar around 1910, succeeding the ineffective administration of Dejazmach Balcha Safo.

On 3 August 1911, Tafari married Menen Asfaw, niece of Lij Iyasu, the heir to the Ethiopian throne. Menen, aged 22, had two prior marriages, while Tafari, 19, had one. Their union, lasting 50 years, was seen as a political alliance, though family accounts emphasized mutual consent. Selassie praised Menen as a woman without malice.

Regency and Deposition of Lij Iyasu

Tafari played a key role in the movement to depose Lij Iyasu, designated but uncrowned emperor from 1913 to 1916. Iyasu’s controversial behavior, including a perceived shift toward Islam, alienated Ethiopian Orthodox leaders and nobles. On 27 September 1916, Iyasu was deposed, with support from conservative and progressive factions. Empress Zewditu, Menelik II’s daughter, was named ruler, and Tafari was appointed Crown Prince and Regent Plenipotentiary, becoming the de facto ruler.

Although Iyasu briefly evaded capture and his father, Negus Mikael, attempted to restore him, the Battle of Segale on 27 October 1916 ended those efforts. Tafari’s growing influence contrasted with Zewditu’s focus on religious duties, allowing him to consolidate power.

Modernization and International Recognition

During his regency, Tafari advanced modernization policies initiated by Menelik II, including Ethiopia’s admission to the League of Nations in 1923 by committing to abolish slavery. While prior emperors had proclaimed an end to slavery, the practice persisted into Selassie’s reign, with an estimated two million slaves in the early 1930s.

Tafari survived the 1918 flu pandemic despite being prone to illness. His limited resources initially hindered governance, but his influence expanded as Empress Zewditu’s authority waned, paving the way for his future reign.

Haile Selassie I’s Travels Abroad

In 1924, Ras Tafari embarked on a tour of Europe and the Middle East, visiting Jerusalem, Alexandria, Paris, Luxembourg, Brussels, Amsterdam, Stockholm, London, Geneva, Gibraltar, and Athens. Accompanying him were prominent Ethiopian figures, including Ras Seyum Mangasha of western Tigray, Ras Hailu Tekle Haymanot of Gojjam, Ras Mulugeta Yeggazu of Illubabor, Ras Makonnen Endelkachew, and Blattengeta Heruy Welde Selassie. The primary objective of the journey was to secure Ethiopia’s access to the sea. However, discussions in Paris with the French Foreign Ministry revealed that this ambition would not be realized. Despite this setback, Tafari and his entourage used the opportunity to study European advancements in schools, hospitals, factories, and churches. While adopting many reforms inspired by Europe, Tafari maintained caution to avoid economic imperialism, requiring enterprises to have some degree of local ownership. Reflecting on modernization, he stated, “We need European progress only because we are surrounded by it. That is at once a benefit and a misfortune.”

Tafari’s travels through Europe, the Levant, and Egypt were met with widespread fascination and enthusiasm. His entourage included notable figures like Seyum Mangasha and Hailu Tekle Haymanot, whose fathers had fought in Ethiopia’s victory over Italy at the Battle of Adwa, as well as Mulugeta Yeggazu, who had personally participated in the battle. The Ethiopians’ “Oriental Dignity” and elaborate court dress captivated the media. Adding to the spectacle, Tafari brought a pride of lions, which he gifted to leaders such as French President Alexandre Millerand, British Prime Minister Raymond Poincaré, and King George V, as well as to the Paris Zoological Garden. In exchange for two lions, the United Kingdom returned the imperial crown of Emperor Tewodros II, taken during the 1868 Expedition to Abyssinia, for its delivery to Empress Zewditu.

During the trip, Tafari visited the Armenian monastery in Jerusalem, where he adopted 40 Armenian orphans, survivors of the Armenian Genocide. Known as the “Arba Lijoch” (“forty children”), these orphans received musical training under Tafari’s arrangement and later formed Ethiopia’s imperial brass band.

Haile Selassie I’s Reign

Rise to Power

In 1928, Tafari Makonnen, later known as Haile Selassie, faced a significant challenge to his authority. Dejazmach Balcha Safo, governor of Sidamo Province, defied Tafari’s regulations, withholding revenue and arriving in Addis Ababa with a large armed force. Tafari strategically neutralized Balcha by having Ras Kassa Haile Darge buy off his troops and replaced him as governor. This incident bolstered Empress Zewditu’s political standing, leading her to accuse Tafari of treason. However, a coup attempt by palace reactionaries in September 1928 ended in failure, with Tafari’s forces ultimately prevailing. On October 7, 1928, Zewditu crowned Tafari as Negus (King).

Tafari’s coronation as Negus sparked controversy, as Ethiopian tradition did not support two monarchs ruling from the same location. This situation led to the rebellion of Ras Gugsa Welle, Zewditu’s estranged husband and governor of Begemder Province. In March 1930, Tafari’s forces defeated Gugsa Welle at the Battle of Anchem, where Welle was killed. Zewditu died suddenly on April 2, 1930, reportedly from paratyphoid fever, although rumors suggested she was poisoned or died of shock from her husband’s death.

Coronation as Emperor

Upon Zewditu’s death, Tafari ascended to the throne as Emperor Haile Selassie, proclaimed Neguse Negest (“King of Kings”) of Ethiopia. His coronation on November 2, 1930, at St. George’s Cathedral in Addis Ababa, was an extravagant event attended by global dignitaries, including the Duke of Gloucester, Marshal Louis Franchet d’Espèrey of France, and representatives from Egypt, Turkey, Sweden, Belgium, Japan, and the United States. American travel lecturer Burton Holmes documented the ceremony on film, and British author Evelyn Waugh provided a detailed report. The coronation incurred significant expenses, with reports suggesting costs exceeding $3 million. Haile Selassie distributed lavish gifts, including a gold-encased Bible sent to an American bishop.

Governance and Modernization

On July 16, 1931, Haile Selassie introduced Ethiopia’s first written constitution, which created a bicameral legislature and concentrated power in the hands of the nobility. Although it aimed to transition toward democracy, the constitution limited succession to Selassie’s descendants, excluding other dynastic princes. In 1932, Ethiopia formally absorbed the Sultanate of Jimma after the death of Sultan Abba Jifar II.

Conflict with Italy

During the 1930s, Benito Mussolini’s Fascist regime sought to avenge Italy’s prior defeat in the First Italo-Abyssinian War and unite its colonies in Eritrea and Italian Somaliland by conquering Ethiopia. Following the 1934 Welwel Incident, Haile Selassie mobilized Ethiopian forces, but the technologically superior Italian military, equipped with chemical weapons, launched an invasion in October 1935. Despite initial Ethiopian successes during the “Christmas Offensive,” the Italians ultimately defeated the Ethiopian forces, culminating in the Battle of Maychew in March 1936.

Exile

After Ethiopia’s northern armies were destroyed and Addis Ababa became indefensible, Haile Selassie decided to leave Ethiopia to present his case to the League of Nations. On May 2, 1936, he departed with his family for French Somaliland. Five days later, Italian forces entered Addis Ababa, and Mussolini declared Ethiopia an Italian province, installing Victor Emmanuel III as emperor.

Haile Selassie and his entourage first traveled to Jerusalem, emphasizing their Solomonic Dynasty’s connection to the House of David. From there, they sailed to Gibraltar and eventually reached Geneva to appeal for international support. However, the League of Nations’ “collective security” measures proved ineffective against Italy’s aggression.

Collective Security and the League of Nations, 1936

On May 12, 1936, Haile Selassie addressed the League of Nations to appeal against Italy’s invasion. Italy, in protest, withdrew its delegation. Although fluent in French, Selassie delivered his speech in Amharic, accusing Italy of using chemical weapons against military and civilian targets.

Earlier that year, Time magazine named Selassie “Man of the Year” for 1935, and his speech in June 1936 made him a global symbol for anti-fascists. Despite this recognition, he failed to secure the international support he needed. The League imposed only partial sanctions on Italy, and key nations recognized Italy’s occupation by 1937, except for six countries, including the Soviet Union and the United States.

Exile

During his exile from 1936 to 1941, Selassie lived in Fairfield House, Bath, England. He spent his days walking with Kassa Haile Darge and studying diplomatic history. It was during this period that he began his 90,000-word autobiography. Before settling in Bath, he briefly stayed in Worthing and Wimbledon.

A bust commemorating Selassie’s time in Wimbledon became a pilgrimage site for the Rastafari community until it was destroyed in 2020. During his stay in Malvern, his family attended local schools, and he visited Holy Trinity Church. A blue plaque was unveiled in Malvern in 2011, with Rastafari representatives participating in the ceremony.

Selassie countered Italian propaganda during his exile, condemning the desecration of religious sites and artifacts and speaking out against Italian atrocities. His appeals for international intervention were mostly ignored until Italy joined World War II on the German side in 1940.

Support for Ethiopia grew among African-American organizations, and Selassie addressed the American public in 1937, despite suffering a fractured knee in an accident. His address emphasized diplomacy and goodwill, linking Christianity with the League of Nations’ principles.

Selassie faced personal tragedies during this time. His two sons-in-law were executed by the Italians, and his daughter Romanework died in captivity. Another daughter, Tsehai, died in childbirth after his return to Ethiopia. Following his restoration, Selassie donated Fairfield House to Bath as a residence for the elderly.

1940s and 1950s

During the East African Campaign in 1941, Selassie returned to Ethiopia with the support of British and Ethiopian forces. On May 5, 1941, five years after the Italian occupation began, he re-entered Addis Ababa and urged Ethiopians to avoid retaliatory violence.

In 1942, Selassie officially abolished slavery, imposing severe penalties for violations. After World War II, Ethiopia joined the United Nations and expanded its territory with the Ogaden region and Eritrea’s federation under Ethiopian administration.

Despite attempts at modernization, Selassie struggled to implement reforms due to resistance from the nobility and clergy. Efforts to introduce progressive taxes were blocked, and land taxes often burdened peasants.

Selassie also worked toward the autocephaly of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, achieving independence from the Coptic Church in 1959. Additionally, he introduced reforms to limit church privileges and taxed church lands.

In foreign affairs, Selassie maintained Ethiopia’s alignment with collective security. Ethiopian troops participated in the Korean War, and he supported African decolonization. He fostered cordial relations with global leaders, including Queen Elizabeth II, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Jawaharlal Nehru.

Domestically, Selassie faced unrest, including a rebellion in Harar in 1948, which was violently suppressed. Hararis, who had been promised autonomy, protested against Amhara dominance and Selassie’s policies.

During his Silver Jubilee in 1955, Selassie introduced a revised constitution granting limited political participation while maintaining his authority. Educational reforms and modernization efforts followed, but Ethiopia remained semi-feudal, with peasants bearing heavy burdens.

Famine and Philanthropy

In 1958, a famine in Tigray province killed an estimated 100,000 people before it ended in 1961. The government mobilized relief efforts, and Selassie personally donated grain. However, the crisis highlighted the country’s vulnerabilities to natural disasters and epidemics.

Selassie maintained international goodwill through gestures such as donating aid to Britain during its 1947 floods, underscoring his commitment to collective security and global cooperation

Haile Selassie I Reign: Key Events and Milestones

1960s

During the Congo Crisis of 1960, Haile Selassie contributed Ethiopian troops to the United Nations peacekeeping force under Security Council Resolution 143. However, while on a state visit to Brazil on December 13, 1960, an imperial guard coup briefly declared his son, Asfa Wossen, as emperor. This attempt, denounced by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and crushed by the army and police, was pivotal as it marked the first time Ethiopians questioned the monarchy’s rule without public consent. The aftermath saw increased student advocacy for the peasantry, spurring Selassie to implement reforms, including land grants to political groups and officials.

Selassie maintained strong ties with the West and advocated for African decolonization. Eritrea’s political future was contentious, with the United Nations eventually federating it with Ethiopia through Resolution 390 (V) in 1950. Tensions later escalated into the Eritrean War of Independence (1961–1991). In 1963, Selassie oversaw the creation of the Organization of African Unity (OAU), becoming its first chairperson and mediating regional disputes. His vision of a United States of Africa influenced future leaders.

Domestic challenges included the Bale revolt in 1963, spurred by tax grievances and external support from Somalia. Ethiopian forces, backed by U.S. and U.K. allies, quelled the insurgency after six years. Selassie’s foreign policy was marked by his advocacy for peace, as seen in his 1963 United Nations speech and his opposition to the Vietnam War. He also sought progressive tax reforms in 1966, facing resistance that highlighted growing unrest among landowners and the nobility.

Throughout the decade, Selassie balanced foreign diplomacy with internal reforms. He attended significant global events, including the funerals of U.S. President John F. Kennedy and French leader Charles de Gaulle, and met numerous world leaders, including Mao Zedong in China.

1970s

As Ethiopia’s longest-serving head of state, Selassie retained international prestige but faced mounting domestic issues. Student protests, fueled by exposure to leftist ideologies, and resistance from conservative institutions hindered his land reforms. Ethiopia received significant foreign aid, with $140 million allocated to the military and $240 million for economic development. Despite these efforts, civil liberties remained restricted, and human rights abuses increased during conflicts with Eritrean separatists.

Famine struck Ethiopia, particularly Wollo and Tigray, between 1972 and 1974, leading to tens of thousands of deaths. Reports conflict on whether Selassie fully understood the famine’s severity. The crisis, compounded by corrupt officials, rising oil prices, and unemployment, eroded public support. Military discontent grew, culminating in the resignation of Prime Minister Aklilu Habte-Wold in 1974, replaced by Endelkachew Makonnen.

The Derg, a military committee, capitalized on the unrest to oust Selassie on September 12, 1974. The 82-year-old emperor was placed under house arrest, and much of his family was imprisoned. The Derg’s consolidation of power led to the execution of 60 former officials, including Selassie’s grandson, Rear Admiral Iskinder Desta, in what became known as “Black Saturday.” The monarchy’s legitimacy was formally revoked, ending the Solomonic dynasty.

Selassie’s final years were marked by imprisonment and political isolation, with the collapse of his regime symbolizing a broader shift in Ethiopian governance. His legacy, while complex, remains a significant chapter in Ethiopia’s history.

Haile Selassie I

Assassination and Burial

On August 27, 1975, Haile Selassie was killed by military officers of the Derg regime, a fact concealed for two decades. The next day, state media announced his death, attributing it to “respiratory failure” from complications related to a prostate operation. However, Dr. Asrat Woldeyes refuted this, stating there were no complications and that Selassie was in good health prior to his death. The alleged operation had taken place months earlier.

In 1994, an Ethiopian court convicted former Derg officers of strangling Selassie in his bed. Three years after the fall of the Derg regime, these officers were charged with genocide and murder, with documents confirming a high-level assassination order. The authenticity of these documents was verified by former Derg members.

Selassie’s remains were discovered in 1992 under a concrete slab on the palace grounds. His coffin was housed in Bhata Church until 2000, when he was given a funeral at Holy Trinity Cathedral in Addis Ababa. However, the government refrained from declaring it an official imperial ceremony, possibly to avoid politically empowering royalists. Prominent Rastafari figures, including Rita Marley, attended, but many Rastafari rejected the event, disputing the remains’ authenticity and debating whether Selassie truly died in 1975.

Rastafari Messiah

Selassie is venerated as God incarnate by some Rastafari followers, a movement emerging in Jamaica during the 1930s. The title “Ras Tafari” reflects his pre-imperial name and leadership, and he is seen as a messiah who will liberate Africa and its diaspora. His titles, including “Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah” and “King of Kings,” along with his lineage from Solomon and Sheba, affirm Rastafari beliefs rooted in biblical prophecies. Reports of his coronation in Time magazine further inspired these beliefs, and Selassie’s philosophy influenced the movement.

In 1961, Selassie met a Jamaican delegation to discuss repatriation and assured his support. His visit to Jamaica in 1966 drew over 100,000 Rastafari to greet him, marking a pivotal moment celebrated as Grounation Day. Despite the authorities’ concerns, Selassie never dismissed Rastafari beliefs and even presented gold medallions to their elders. This respectful acknowledgment solidified his symbolic role within the movement.

Rita Marley converted to Rastafari after witnessing Selassie, claiming to see a stigmata on his hand. Rastafari gained global recognition through Bob Marley’s influence, with songs like “Iron Lion Zion” referencing Selassie.

Selassie’s Position

In a 1967 CBC interview, Selassie denied claims of divinity. However, many Rastafari interpreted his statements differently, viewing them as neither affirmations nor denials. After returning to Ethiopia, Selassie sent Archbishop Abuna Yesehaq Mandefro to the Caribbean to integrate Rastafari into the Ethiopian church, addressing growing interest in its establishment.

In 1948, Selassie granted 500 hectares of land in Shashamane for African diaspora supporters. Several Rastafari families settled there, though it caused tensions with local Oromo communities.

Residences and Finances

The Jubilee Palace, Selassie’s official residence from 1955, remains a historical landmark in Addis Ababa. Allegations during the 1974 revolution claimed Selassie amassed $11 billion, but records from 1959 show his net worth was only £22,000. Derg officials also accused him of hoarding wealth in Swiss banks, though these claims remain unverified.

Selassie’s possessions included a valuable fleet of cars, many received as diplomatic gifts, and a rare Patek Philippe watch estimated to exceed $1 million, which was later withdrawn from auction following disputes.

Personal Life

Arts and Literature

Haile Selassie championed the advancement of Ethiopian art, believing it was crucial to the nation’s reconstruction. He encouraged a contemporary approach to traditional art forms, particularly those associated with the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. Selassie supported artists like Afewerk Tekle, who gained international recognition and portrayed Ethiopian life through his works. He also funded art programs and provided scholarships, benefiting artists such as Ale Felege Selam and Agegnehu Engida. Selassie often visited Bishoftu to appreciate the work of Ethiopian painters, including Lemma Guya, whose military-themed art gained his admiration. Guya later joined the Air Force while continuing his artistic pursuits under Selassie’s patronage.

Selassie also played a pivotal role in the performing arts, establishing Ethiopia’s first theater house in 1935 and inaugurating the National Theatre in Addis Ababa in 1955. His literary contribution includes the autobiography My Life and Ethiopia’s Progress, written during and after his exile in the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, though parts of it were likely compiled by officials.

Sports

Under Selassie’s reign, Ethiopia saw a rise in international sports participation. He fostered the growth of national organizations like the Ethiopian Football Federation and the basketball team. Ethiopia’s victory in its first African Cup of Nations was celebrated with Selassie presenting the AFCON trophy. Selassie personally honored Olympians like Abebe Bikila, awarding him the Star of Ethiopia and the Order of Menelik II. Other athletes, such as Mamo Wolde, also received Selassie’s direct encouragement and support.

Religion

Raised in Ethiopia’s traditional Christian heritage, Selassie was a devout follower of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church. His reign saw efforts to unify Oriental Orthodox communities, including those in Egypt, Armenia, and Syria. Despite these efforts, Selassie supported the Ethiopian Church’s autonomy when it was granted its Patriarch. His diplomatic relations with other religious leaders, such as Pope Cyril VI of Alexandria, strengthened inter-Orthodox ties.

Under his rule, Ethiopia’s legal system became more inclusive, granting Islamic courts jurisdiction over Muslim-related matters. Selassie also engaged directly with Ethiopia’s Muslim community, demonstrating respect for its leaders’ concerns.

Family

As the head of the Royal Family, Selassie upheld his authority over household matters. Unlike earlier Ethiopian monarchs, he extended political roles to his immediate family. His grandson, Rear Admiral Iskinder Desta, served in the Ethiopian Navy. However, there were claims—unverified—that Desta pressured Selassie to alter the line of succession.

In education, Selassie ensured his grandchildren attended elite institutions globally, including Gordonstoun School in the UK and Columbia University in the US.

Legacy

Public Image and Media

During the 1930s and 1940s, Selassie was celebrated globally, especially during Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia. Western media, including Time magazine, which named him “Man of the Year” in 1935, depicted him as a symbol of resistance against fascism and a beacon of African unity. His post-World War II initiatives, like establishing Addis Ababa University and the Organisation of African Unity, further cemented his legacy as a modernizer and anti-colonial leader.

However, by the 1970s, economic hardship and famine tarnished his image. Public dissatisfaction with his governance led to mass protests and, eventually, his removal from power.

Selassie’s contributions to education, Pan-Africanism, and global diplomacy remain significant, earning him recognition as one of history’s key political figures. Time ranked him among the “Top 25 Political Icons” of all time.

Memorials

Numerous tributes to Selassie exist, particularly in Ethiopia, where a 2019 memorial was unveiled at the African Union headquarters honoring his efforts in Pan-Africanism. Unity Park in Addis Ababa features a wax statue of him, while schools and roads in countries like Jamaica and Kenya bear his name. However, his legacy remains contentious; in 2020, a bust of Selassie was destroyed by protestors reacting to the killing of Oromo singer Hachalu Hundessa.

Selassie’s impact extends into popular culture, with his depiction in video games, songs, and films. Notable works include Teddy Afro’s nationalistic song “Haile Selassie” and a 2024 biopic where Selassie appears in Rastafarian lore. His image has been immortalized through art and photography, ensuring his place in history as a complex and transformative figure.

Titles and Honours of Haile Selassie

Over his 58 years of leadership (1916–1974) as Regent and later Emperor of Ethiopia, Haile Selassie received a vast array of honours and decorations from Ethiopia and other nations. His extensive travels and diplomatic engagements made him one of the most decorated individuals in history. The Guinness Book of World Records once recognized him as the most decorated person ever.

Titles and Styles

- 23 July 1892 – 1 November 1905: Lij Tafari Makonnen

- 1 November 1905 – 11 February 1917: Dejazmach Tafari Makonnen

- 11 February 1917 – 7 October 1928: Balemulu Silt’an Enderase Le’ul-Ras Tafari Makonnen

- 7 October 1928 – 2 November 1930: Negus Tafari Makonnen

- 2 November 1930 – 12 September 1974: By the Conquering Lion of Judah, His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie I, King of Kings, Lord of Lords, Elect of God, 134th Christian ruler of Ethiopia.

- On 21 January 1965, he was venerated as “Defender of the Faith” by Oriental Orthodox Church Patriarchs.

National Orders

- Chief Commander, Order of the Star of Ethiopia (1909)

- Grand Collar, Order of Solomon (1930)

- Grand Cordon, Orders of the Seal of Solomon, Queen of Sheba, Holy Trinity, Menelik II, and Fidelity.

Foreign Orders

Haile Selassie received numerous foreign honours, including:

- United Kingdom: Honorary Knight Grand Cross of the Orders of St. Michael and St. George (1917), Royal Victorian Order (1930), and the Order of the Bath (1924); Stranger Knight Companion of the Order of the Garter (1954).

- Italy: Knight Grand Cross of the Orders of Saints Maurice and Lazarus (1924) and the Crown of Italy (1917).

- France: Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour (1924).

- Japan: Collar of the Order of the Chrysanthemum (1956).

- United States: Chief Commander of the Legion of Merit (1945).

- Portugal: Grand Cross with Collar, Order of the Tower and Sword (1925).

- Additional decorations from Belgium, Greece, Germany, Norway, Sweden, and numerous other countries.

Foreign Decorations and Medals

- France: Croix de Guerre (1945), Military Medal (1954).

- United Kingdom: Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Medal (1953).

- Iran: Medals commemorating the 2500th Anniversary of the Persian Empire and the Shah’s Coronation.

- Other medals from the UN, Yugoslavia, Jamaica, and more.

Other Distinctions

Haile Selassie was an honorary citizen of various countries, including Yugoslavia and Malawi. He also received titles such as Great Buffalo High Chief (USA) and Great King of Malawi.

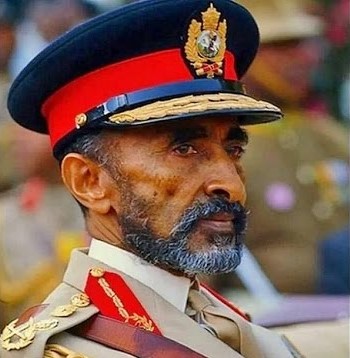

Military Ranks

- Field Marshal, Ethiopian Army

- Admiral of the Fleet, Ethiopian Navy

- Marshal of the Ethiopian Air Force

Foreign Rank: Honorary Field Marshal, British Army (1965).

Haile Selassie’s legacy as a leader, diplomat, and decorated figure remains unparalleled in modern history.

Thank you for reading.

𝐂𝐨𝐧𝐧𝐞𝐜𝐭 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝐮𝐬:

Website: africarized.kelvinjasi.net Subscribe to our

YouTube channel: https://www.youtube.com/@Africarized?sub_confirmation=1

Follow us on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/africarized/

Follow us on TikTok: https://www.tiktok.com/@africarized

Follow us on Instagram: https://www.tiktok.com/@africarized

Follow us on X: https://x.com/Africarized